Will Hagle doesn’t mess with Texas, but he doesn’t fuck with it either.

POV: Your house just burned down. A victim of an ecological disaster that we describe so casually as “wildfire season.” In your house, which is technically owned by a bank, was your vinyl collection. Your 15 lb. stack of never-played Gordon Lightfoot discs. Two identical Dan Fogelberg LPs, both of them scratched. The $49 Velvet Underground Urban Outfitters edition that you’d listen to while searching service jobs on Craigslist, while ranting to your cat-sitter about how the bank that would eventually give you a loan for your now-burnt-down house caused the subprime mortgage crisis and subsequent recession that made Georgetown sociology graduates like you unfit for careers offering a secure financial future. Your copy of DAMN. With the song that goes “bitch all my grandma’s dead!” Your dead grandma’s Dinah Washington LP. All of it, turned to ash.

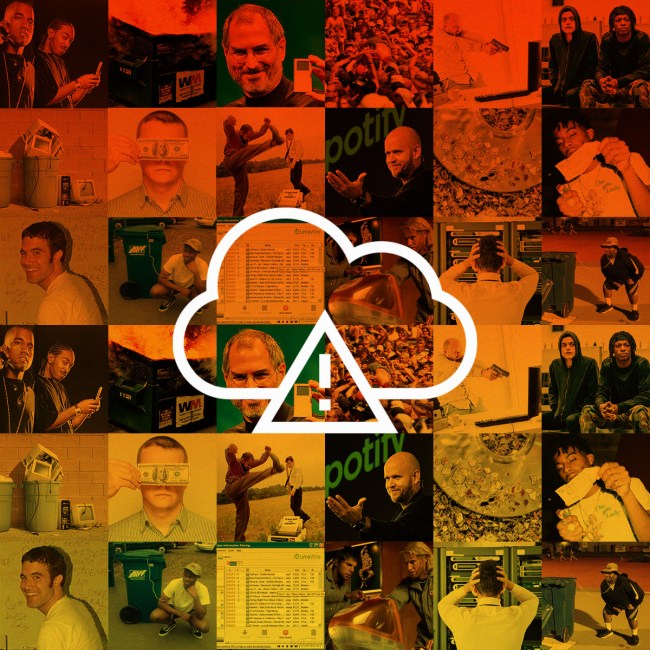

POV: You wake up in 2018 to the news that a server migration issue caused Myspace.com to lose 50 million songs forever. You were one of the 14 million artists who uploaded music prior to 2015, when the site was still semi-relevant. Your ska-punk anthem “I Left My Wallet In El Skagundo” will never be heard again. Unless your bassist saved it on a thumb drive. But you saw him at your high school reunion and you only talked about how the songs were still up on Myspace, even with the redesign, and yeah we never listened to it, but wasn’t that hilarious? If he had it on a hard drive he would have mentioned it, wouldn’t he? Anyways, he’s a hardcore MAGA guy now, and your drummer died of an overdose years ago. The song is gone. Deleted. A tiny loss in a tremendous casualty. But it’s probably for the best if your fiancé never discovers your ska past, anyways. But man, that was a great era. Myspace. Skanking. That was when music was music. RIP.

POV: It’s the early 2000s and you just blamed Napster/Limewire/Kazaa on the computer virus that fried your family PC, to detract from your suspected culprit: the pixelated boobs you’ve been pulling up in the middle of the night. The guy at the computer store wipes the machine clean and when you reinstall Windows the only program allowed is AOL. “If you want to listen to music you can buy it with your own money,” your mother says, sounding conspicuously like Lars Ulrich. You search the racks at Best Buy and Circuit City but you can’t find the DJ Assault remix of “Ass N Titties” anywhere. You don’t know if you will ever hear the live version of Limp Bizkit’s “Rollin” ever again.

POV: After 12 years of gleefully downloading albums and organizing them in iTunes, what.cd is suddenly seized by the feds and taken offline forever. A torrent of sadness washes over you, invisible behind your mask.

POV: Kim Dotcom is arrested, Megaupload and the equivalent knockoffs stop working, and the blogspots you perused fade away to the rise of streaming services, which are convenient and amazing but invent new problems and don’t replace the desire to physically own music, which is nice and great until you remember that music could burn down or be destroyed too, like everything.

POV: “Meet the Flockers” is canceled.

Point being, no one wants their music collection to be deleted. No one wants their preferred method of discovery to disappear. Yet both happen repeatedly, consistently over the course of time, in multiple forms. This is a universal human experience.

The meme reactions get much happier, however, once you accept that the internet—despite its ability to document its own past—offers, at best, a temporary experience. Like life IRL, it pulls us constantly to the past or future. Pulling up old photos on Friendaversaries. Reminding you to check Ticketmaster, because covid’s over and concerts are back this fall. But also like life IRL, living online is less anxiety-ridden when you accept that nothing is real, you couldn’t possibly “own” music, and every time you hear a song might be the last time you’ll hear it.

This blog post, which may or may not be around five years post-publication, was inspired by this tweet, which definitely won’t be deleted because it went so viral and now has been screenshotted:

“Possibly the single greatest loss of art in history” is debatable, and likely biased based on the author’s personal nostalgia for the platform. But that’s not the point. The point is that everyone who has acquired music online has felt this way about something. The thread goes on to warn readers about how corporations don’t care about art or people.

Without reading the replies, it seems obvious that many of them ridicule the author for being upset about this. They don’t think that the Myspace mishap was a big deal. Which goes back to the original tweet in the thread. “It was in the news for maybe a day. Possibly the greatest loss of art in history and just. That’s it.”

The overall apathetic response to Myspace’s blunder exemplifies how we have already been conditioned to accept the temporary nature of what we put online. “Accidents” like this are initially sad, but there is nothing we can do about them, so we move on and make fun of other people who can’t get over it.

But because I relate to people like @yiffpolice, and because so many people engaged with this post, the opposite could also be true. People don’t want to accept that the music we created and loved could be so carelessly erased by a corporation that no longer finds them financially valuable. We simply have to.

In the context of human history, however, recorded music has barely yet registered as existing. Music itself has been around, it seems, forever. Adam seduced Eve with God’s favorite R&B song, didn’t he (“Birthday Sex”)? But back then, when jesters were playing fiddle for the royal court or whatever, you heard a song once and never heard it again. You didn’t own it. Music was an in-the-moment, collective experience for those who were around to hear it. Of course this lineage continues today with, say, the bucket boys in Chicago or random old dudes busking on bridges in Prague. But “music,” as we tend to conceptualize it in discussions online, mostly refers to the recorded form.

The history of recorded music can and will be summed up in one quick paragraph. Edison and his competitors sold cylinder phonographs in the 1880s and 1890s. New York City threw a concert where people showed up to watch a record player playing an orchestral piece on stage, and were amazed that they didn’t need live instruments (don’t fact-check me on this, but I heard about it once). Music media has undergone multiple transformations since then, from vinyl to cassettes to CDs to streaming. But since the end of the 19th century, the directional flow of music creation and consumption has largely run the same way. A corporation or company distributes an artist’s recorded music to individuals for personal ownership in exchange for a fee. Streaming seems different, but it’s the same. You just pay a smaller amount for infinite access to a corporation’s collection.

The internet does offer the potential to alter this dynamic. Many have tried, with varying degrees of success. Aforementioned file-sharing and torrent services were on to something, but failed to deconstruct our ingrained concept of music as an industry. Blockchain could probably help somehow, but don’t ask me for details.

Although the internet has been colonized by monopolistic corporations, the idea behind it still inherently “disrupts” the top-down flow of distribution. Radiohead or Bomb the Music Industry! can do direct-to-fan sales. Artists can drop links to their albums. No artist needs to be reliant on people exchanging money for ownership of recorded music. They can make money on the road, performing face to face like the old days. Online they are beholden only to algorithms, and only if they want more people to discover them.

The internet, in its purest form, returns us from the top-down approach of the 20th century to the face-to-faceness of yesteryear, with computers serving as an intermediary. It could allow us to reimagine what music itself means. Could detach us from our associations of music to either physical or incorporeal ownership. Could allow music to be freely shared back and forth and eradicate the idea of intellectual property.

It’s been around for decades, though, and the trajectory doesn’t look promising. Music is still very much an industry, and industries are very much necessary for people to survive IRL and whatnot. In this system, corporations will do what they have to in order to ensure that the flow of distribution stays tilted in their favor. The internet will continue to be a skewed, addicting continuation of 20th century consumption.

So if no one’s going to reinvent music or redesign the internet, the best we can do is accept our reality. Like the tweeter said, corporations won’t preserve “art.” But Myspace didn’t have anything to do with “art.” No “art” was actually lost. The mp3s were never more than files on a server. The Myspace era itself was, through the active participation of artists and fans who interacted on the platform pre-’15, the “art.” Collectible only in our fading memories. Yes I will continue to use quotation marks around the word “art,” because it’s such a subjective term.

From my POV, tying yourself to access to or ownership of recorded music only leads to heartbreak when the facade-patterned rugs of access and ownership are pulled from under you, by a corporation or wildfire or anything. We shouldn’t stop collecting recorded music, but we have to be prepared for it to disappear. Recorded music represents a tiny fraction of the “art”form’s existence, and if one day it all goes away, music will continue, and we will feel like this: