Pass Sam Kelly the hookah!

America has traditionally liked to view itself as the world’s primary arbiter of taste, dictator of trends and provider of the cultural blueprint for other nations to follow. Pundits proudly, insistently declare that “culture is America’s greatest export,” ignoring that the examples they cite are largely based in America’s black, brown, queer, and immigrant communities. Basketball didn’t become a worldwide phenomenon until Michael Jordan stepped onto the court. Kanye West has influenced global fashion trends more so than Garth Brooks or Sting. You get my point.

The flip side of America’s self-image as creator of culture is its stubborn reluctance to truly engage with art created outside of its borders. From the Beatles to Adele, and Celine Dion to Drake, the international musicians to secure long-term footholds in America’s pop stratosphere have usually been white Brits or Canadians. Almost everyone else has been here today, gone tomorrow.

How long has grime “been about to break into” the American market? When Dizzee Rascal released Boy in Da Corner, East London was heralded as “hip-hop’s next great international outpost,” but 16 years later the closest grime has come to a hit in the States is “Mans Not Hot.” K-Pop has developed a massive fanbase in the States, but you won’t exactly hear BTS on the radio. America views foreign artists as talents to be respected from a distance, at best, and a halloween costume, at worst.

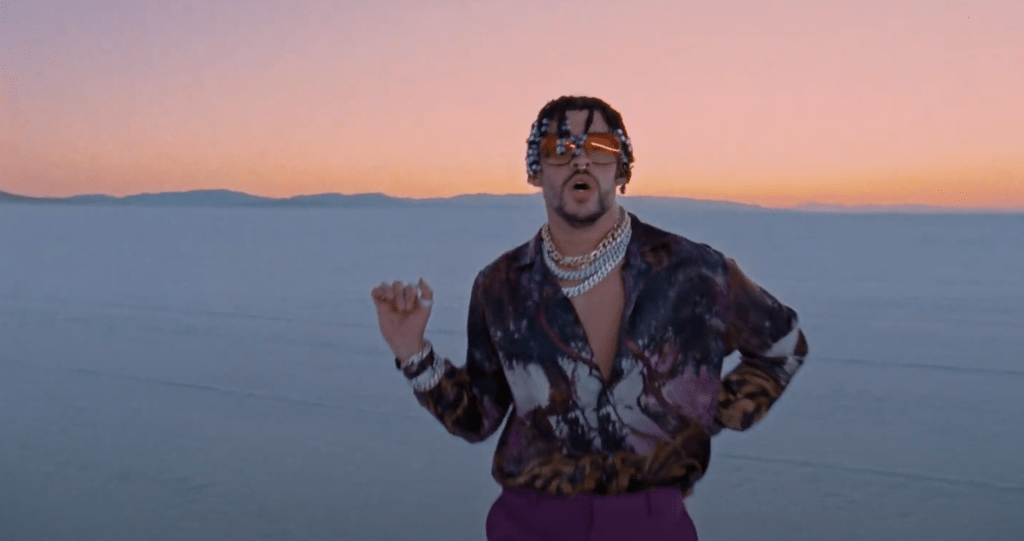

Enter Bad Bunny, the 24-year-old from Vega Baja, Puerto Rico who’s already been crowned the “King of Latin Trap,” though his talents span a wide range of genres. In 2017, he rose to fame in Latin America on a handful of singles and features, and the year following burst into the American popular consciousness with an arresting feature on Cardi B’s “I Like It.” Since then, Bad Bunny has become the face of urbano (the term used to encompass Latinx pop forms like reggaeton, dembow, and latin trap) in the United States, and garnered a sizable following of Spanish and non-Spanish speaking fans alike.

On the surface, it would seem that Bad Bunny has nailed the crossover, and secured himself a place on America’s pop playing field. The only problem is, we’ve seen this before. International artists blow up all the time, but the fire fizzles out pretty quickly. Americans love the novelty of a sound they haven’t heard before, but once an artist starts to assert their craft as legitimate, audiences shrug it off as belonging to the other. What gives Bad Bunny a chance at breaking from this tradition is the sheer unpredictability of his music; if he’s not erasing the lines that divide the music of different cultures, then he’s at least blurring them.

Despite their proximity to the United States, Latinx artists have not been exempt from its history of marginalization. There have, of course, been plenty that have made it big in the States, but they’ve done so primarily within the parameters of this country’s large, diverse Latinx population. They rarely get included in the dominant cultural narrative, and so little room has been left for those who don’t sing in this country’s dominant language.

Hector Lavoe, for example, is one of the most influential artists of his era: the embodiment of salsa music and the soundtrack of a generation for New York’s sizable Puerto Rican community. The only Grammy nod he ever received was in 1987 for Strikes Back, nominated for Best Tropical Latin Performance. Whatever that means.

Celia Cruz, widely recognized as the Queen of Salsa, was nominated for 14 Grammys throughout her career, and every single one fell under a “Tropical” or “Latin” category (unless you count Wyclef Jean’s remix of “Guantanamera, which was nominated for Best Rap Performance by a Duo or Group in 1997).

Latinx artists are recognized in America, but only in their own distinct universe, never considered in the same arena as those from the continental United States.

For a minute in 1999, it looked like things were about to change. The “Latin Explosion,” as it was called, saw an infusion of Spanish guitar and salsa tropes into mainstream pop. Over the course of a few months, Ricky Martin filled arenas from New York to Salt Lake, Jennifer Lopez went triple-platinum with her debut album On the 6, and Enrique Iglesias’ “Bailamos” topped the Billboard Hot 100. Latinx artists were dominating the airwaves and redefining the sound of pop as it entered the new millenium, one Spanglish hook at a time. Then, as quickly as it had started, the fire died out. The problem with “explosions,” see, is that they’re short-lived. Who from that era, besides J-Lo, was really able to capitalize on their popularity in the States for more than a year or two?

20 years later, Latin music is seeing another “explosion” in the form of urbano. The difference between this explosion and the last is that this one is spearheaded by Bad Bunny. He could have cornered the market in Latin Trap after the success of his breakout singles, “Diles” and “Soy Peor,” but instead he opted for an alternate route, and it might be the reason he avoids the pitfalls that have befallen crossover acts in the past. From blistering dembow to sadboy ballads to buoyant reggeaton, Bad Bunny has fostered an aesthetic so flexible that it can’t be tied to one particular sound. In the process, he’s established himself as one of the most versatile musicians in the world.

This is one of the few instances in which the oft-cited comparison to Drake shouldn’t be disregarded too quickly; Bad Bunny may be the first artist since Drake’s ascent in the early ‘10s that is so completely untethered to one genre, who has the same knack for catchy hooks, stylistic fluidity, and candid lyricism that make us think he’s one of us, though his larger than life persona suggests otherwise. More importantly, these qualities make him feel like one of those rare talents with the potential for real staying power in America’s volatile pop zeitgeist. Given how quickly Americans have disregarded international artists in the past, that would be no small feat.

The high points on Bad Bunny’s debut album, X 100PRE, come from all angles. He weaves through moods and genres quickly and with precision, and the result is a gloriously unpredictable and engaging collection of tracks. Popular Twitter deity @yc jokingly tweeted that “La Romana is Latin Trap’s Sicko Mode,” but he’s not wrong. One of the best songs on the album, “La Romana” begins with crisp, bachata-driven trap, before cutting out suddenly at the height of its catchiness, giving way to pummeling dembow featuring Dominican dembow icon El Alfa. “Otra Noche En Miami,” for its part, approaches on a lower key. With its gentle, melancholic tone, dreamy synths, and powerful hook, it exudes a real “my life a movie” air upon the listener as they ride the bus home from work. It would have been perfect in Miami Vice.

And, as he’s so often done before, Bad Bunny doesn’t miss an opportunity to embrace his sadboy tendencies. With songs like “NI BIEN NI MAL” and “Solo De Mí” so willingly wallowing in their heartbreak, you have to wonder if the only reason they’re not considered emo rap is that Bad Bunny isn’t a white American with face tats (may Lil Peep rest in peace). “Solo De Mí” may have a dembow beat, but lines about raising bottles at your ex’s wake are blatantly melodramatic in any language. “NI BIEN NI MAL,” for it’s part, revels in the aftermath of a broken relationship and what that entails. By the end of the song, he’s run through all the classic emo tropes: drugs to ease the pain, assurances of “you’ll-miss-me-when-I’m-gone,” and promises to learn from his mistakes i.e. you. Bad Bunny is the next great emo rapper, confirmed.

In the past, one of the greatest obstacles facing international artists has been the critics and marketers who define them by their difference, and so pigeonhole them into certain sounds. This may work in the artist’s favor in the short term, (see: “Gasolina,” the Justin Bieber remix of “Despacito,” even “La Macarena”), but once American audiences get bored they move on to the next big thing and the artist, however talented they may be, becomes a fad in the States.

If there’s anyone who can overcome being tokenized in this way, it’s Bad Bunny. His sound is too singular, his personality too eclectic, for him to be written off as a one-hit wonder in the casually racist way many of his predecessors have. Whereas many Latinx artists in the past have had to record entire albums in English to find an audience in the States, Bad Bunny has carved into the public consciousness in nothing but his native language. Even more impressively, he’s done so without having to rely on one popular song, the strength of which would naturally fade after time. I mean, he’s only released one album and a slew of singles, and has still managed to make it this far without one definitive, career defining hit. Everyone seems to have a different favorite song.

Secondly, Bad Bunny has more control over his music and his image than previous crossover successes. That he’s not willing to compromise either to appeal to overseas audiences only increases his longevity as a bonafide superstar. He’s not throwing conga drums on any old pop song and calling it “different,” or performing some stereotype of a Latin lover. If his freewheeling musical style is any indication, he’s just doing him. Americans loved hearing Ricky Martin sing about “living ‘la vida loca,’” but that sort of pandering rarely has any staying power; our culture is too easily distracted to latch on to something so inauthentic for more than a minute.

Additionally, Martin and other stars from the first Latin Explosion were blatantly marketed with an eye towards white America’s propensity for exoticism and fetishization. Bad Bunny, however, came up independently, first through Soundcloud, and then the homegrown Puerto Rican label HearThisMusic. Once he started to feel stifled by HearThisMusic, he left them. Bad Bunny has made it big on his own terms and consequently he’s been treated with nuance and respect by some of America’s most prominent critics, something that hasn’t always been guaranteed to crossovers.

Still, one “best song of the year” ranking in the New York Times isn’t enough to undo the decades of conditioning the American public has undergone with regards to crossover culture and how it views Latinx artists. Particularly in the streaming arena, Bad Bunny is still being tokenized as a Latin musician. He’s heavily featured in Latin-centric playlists but consistently left out of more popular curated ones like Rap Caviar and The A-List: Hip-Hop. This means fewer streams, which have become a major factor in lucrative record deals, and less exposure.

In the week ending February 21st, Bad Bunny’s most-streamed song in the United States was the Drake-featuring “MIA,” which was good for 59th place on Spotify’s weekly charts, while Post Malone took two of the top five spots with “Wow.” and “Sunflower,” respectively. “Wow.” features prominently on both “Rap Caviar” and “The A-List: Hip Hop,” while Bad Bunny doesn’t have a spot on either. With all due respect to Posty, (or not) imagine the streams Bad Bunny would get if a song as hard as “La Romana” got the same treatment.

The next year will be a fascinating one for Bad Bunny and the rest of the urbano movement. If 2018 was urbano’s breakout year, what does that make 2019? In decades past, it would have meant a sharp decline in interest from American audiences, but the air feels a little different this time around. This time, the movement is being led by someone who can’t be pinned to a single sound or narrative. You can’t escape that which you can’t define, and right now that’s working in our favor; anyone with any sense knows that, however you choose to describe it, the stuff that Bad Bunny is making is some of the most compelling music to hit the mainstream in a long time.