Thank you for voting in the Hardest Rap Album of All Time bracket. If this is the first time you’re hearing of the tournament, below you’ll find Deen’s introduction to help you understand why we would host such a thing. Below that you’ll find the writeups for all 35 albums, starting with champion Mobb Deep’s The Infamous in the East region.

An Introduction to the Hardest Rap Bracket

I know you’re probably wondering why anyone cares about anything as niche as the “Hardest Rap Album” ever. Well, I’m not sure I know precisely why either, but I do know that rap is a genre that’s been based on competition since its earliest days. A large chunk of our favorites are rooted in some level of criminality and aggression. Just take a look at your preferred album from rap’s classic canon. If the rappers weren’t doing wild ass shit, they were probably reporting on some wild ass shit. Or letting their imaginations run wild. Try to imagine the development of the genre WITHOUT its most anti-social components. See? You can’t do that. Unless you were born after 2005 and if that’s the case, please close the tab and go do your homework.

As recently as a decade ago (when Kanye showed up), rap fans didn’t really have any time for rappers that didn’t give off some sort of hardness, perhaps as a proxy for the now malleable concept of authenticity. Even in this cream-puff era of rap, the biggest stars aren’t immune from macho posturing & flexing in Nike gloves.

So what are the factors that we considered when seeding our contenders? There were no hard and fast rules because hard and fast rules wouldn’t be gangsta, but we thought about the following criteria:

· Quality: all of these albums are hard but some aren’t classics. Others are. That matters.

· Impact: yeah, it’s hard but have you even heard the shit? Has your significant other heard it? Any hits on that shit?

· Sound: without revealing my personal bias, some production is just harder than other shit by default. Think of the difference between ‘Juicy’ and ‘Machine Gun Funk’. Got it? Good.

· Influence: did other rappers bite shit from the album? Are we gonna or have we celebrated milestones based on the album.

· Consistency: is there a song ‘for the ladies’ on the album? How many R&B hooks show up? If you have to think about it, no bueno.

· Target Demographic: who’d like the album more—you or a stripper?

· Politeness: just how anti-social is this shit?

· Body Count: I refuse to explain this.

EAST REGION

(#1) Mobb Deep’s – The Infamous

We could talk about the overdose of nihilism on every one of The Infamous’ songs or about how the callowness of P and Hav’s voices added an unsettling amount of menace to each verse or how our protagonists managed to provide a panoramic view of the nasty, brutish and short lives young men lived in Queensbridge, New York circa 1994, but I’d be treading familiar ground.

Instead, direct your attention to the sound of the album. The almost entirely self-produced album happens to be home to the chilliest snares in rap history. Yup. Just focus on the snares. You’ll never hear harder snares for as long as you live. Add in the perfectly curated samples (mostly ominous piano loops) and The Infamous essentially aided East Coast rap’s revival and influenced the sound of hardcore rap until NYC fell off. If that ain’t hard, then I don’t know what hard is. There’s a good chance that moron Giuliani heard this shit and decided to start the process that converted NYC from the gulliest American city to the gentrified theme park it is now.

More fun tidbits: There’s a song with a woman on the hook but she’s singing about a manhunt. Q-Tip drops a verse—the most violent one of his career. Nas, Rae and Ghost show up—at the height of their mafioso obsessions. Prodigy threatens to shoot random women—during the FUCKING INTRO. And finally, the crown jewel of the album, “Shook Ones Pt. 2,” served as the single and included the following threat“Rock you in your face, stab your brain with your nosebone . . .” I rest my case. — Mobb Deen

(#8) Public Enemy – It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back

Nothing scares the Powers That Be more than an educated minority with a predilection for militancy. To date, there has been no better audio representation of this fear than Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. Between the intelligent and righteous wrath of Chuck D, the crazy street antics of Flavor Flav and the paramilitary madness of Professor Griff and the S1Ws, Public Enemy was the band most likely to scare the shit out of your parents and politicians alike. Amped on beats by the inimitable Bomb Squad production team, the album somehow managed to be both an aural attack and a funky groove simultaneously. Sure, everybody and their brother was sampling James Brown at the time, but P.E. eschewed the rubbery bass lines and went straight at you with the scronking horns and aggressive guitar licks.

Kicking off with a snippet of a live European gig showcasing alarms and Prof. Griff warning the world that shit’s about to get real, “Bring the Noise” remains one of the greatest opening salvos of any album in any genre. “BASS! HOW LOW CAN YOU GO? DEATH ROW. WHAT A BROTHER KNOW?” is the cannon fire that starts this 60 minute march through the ghettos of their minds.

Topics run the gamut from the crack epidemic (“Night of the Living Baseheads”) to trash television (“She Watch Channel Zero?!”) to media beefs (“Don’t Believe the Hype”). Whereas other “hard” bands were just beginning to figure out what “gangsta” meant (N.W.A. notoriously received a copy of It Takes.. just months before drafting Straight Outta Compton themselves, and the Bomb Squad would be called in to take control of the boards for Ice Cube’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, P.E. was suggesting that the masses (or at least the disenfranchised portion thereof) get their shit together and overthrow the government. Fuck running your block, Public Enemy wanted to change the goddamn world. It gets no harder. — Chris Daly

(#4) Notorious B.I.G. – Ready to Die

Forget about all the other factors for a second. The struggles, both interpersonal and existential. The often crass sexuality. And the hits, my god, those hits. (Eternal house party staple “Big Poppa” and life-affirming rags-to-riches story “Juicy” are songs that will exist as long as people like listening to things that make people feel good, which in our think-piece-obsessed social climate, might not be for very much longer.) Ready to Die was, and still is, hard as an iron curtain, as you might expect from an album that contains a song called “Machine Gun Funk.”

A testament to Christopher Wallace’s gifts as a writer, his debut album created a variety of rough tones. “Things Done Changed” flipped around the romantic worldview of New York as a modern Wild West movie and showed its grisly side; he warns, “Step away with your fist-fight ways” while painting the city’s metamorphosis into a maze of cold brick buildings riddled with bullet holes. The album’s funniest song, “Gimmie the Loot,” includes shooting cops and the infamous line of pregnant women getting held at gunpoint for their #1 Mom pendants. (If the song had just the indelibly delivered line “I’ve been robbing motherfuckers since the slave ships” over and over, it would have been just as good.) “Warning” not only gets a Lil’ Fame shout-out onto MTV, but finds Biggie threatening to explode his potential robbers Boyd Crowder style.

The bleak worldview of the majority of the album, exacerbated by Smalls blowing his own brains out on “Suicidal Thoughts,” with all its abject poverty and nihilism and the idea that its author does not believe in the sanctity of human life, proves one theory about hardness that cannot be disputed: There’s nothing scarier than going up against somebody who feels they have nothing to lose. — Martin Douglas

(#5) Big L – Lifestylez ov da Poor & Dangerous

“So don’t step to this ‘cause I got a live crew / You might be kinda big but they make coffins your size too / I was taught wise / I’m known to extort guys / This ain’t Cali, it’s Harlem nigga, we do walk-by’s.”

Spite incarnate, Big L’s music was forever shadowed by death. Every other line was a blast of threats aimed at enemies, doubters, competitors and anyone who had something to lose. Lamont Coleman was undermining parent’s attempts to raise well-adjusted children, years before Shady gripped a chainsaw. L splattered his bars with an encyclopedia of offensive content and spat them with enough malice to traumatize a Juggalo. Who else would end a song by shouting out murderers, thieves and people with AIDS?

Coleman’s debut was the only full-length album recorded during his short life and he named it in direct opposition to television show Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. As someone who had no time for caviar dreams, Big L was the quintessential disaffected youth. He was too poor to afford a conscience and rarely paused between dome cracking bars to reflect on social issues. Cold angst permeates throughout the record and as a fan of horror films, L relished playing the villain and shocking the listener. While other emcees claimed the means justified the ends, Lamont laughed off constraint and poisoned eardrums with comparisons to the devil.

The power of Lifestylez doesn’t just lie in dark imagery though. Big L was a paradigm of technical ability with internal rhyme schemes and caustic wit. “I got styles you can’t copy bitch, it’s the triple six, In the mix, straight from H-E-double-hockey sticks.” Coleman’s lyrical bloodbath was also backed by D.I.T.C’s production and the album knocks front to back. Unfortunately, Columbia couldn’t predict suburbanites enjoying jokes about killing nuns and found Illmatic’s conscious spin on street-life was easier to market. Big L was dropped a year later and gunned down before he could record a proper follow-up making this project a haunting reminder of the realities of Harlem in 1995. — Jimmy Ness

(#6) DMX – It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot

DMX owns the bark and the snarl. Go ahead, try and match him; you’ll sound foolish. When delivered by Earl Simmons, yaps have the ability to twist your ego like a funhouse mirror. They’re why we’ll be playing the “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem”—a chant so gully that it was last seen dragging “We Dem Boyz” behind a bodega—for as long as evolution maintains mean mugging.

In 1998, Def Jam had two albums top the Billboard charts. One was the star-making turn from a Marcy gentlemen who would go on to be the biggest, and maybe the greatest rapper in the world; the other was an unchained debut from the angriest man in Yonkers. (That’s a high bar.) “One, Two X is coming for you, Three, Four, better lock your door.” Jay topped charts rapping over Annie, D ends a party song “Talk is cheap, Motherfucker!” using (what sounds like) the gun from The Jackal. Then a technically impressive scumbag emerged from the 313, to change hip-hop forever.

As Eminem verified and cashed in on the commercial viability of antisocial raps, hip-hop’s post-Y2K priorities turned towards the suburbs and, later, ringtone pop. DMX was a dog no one wanted. There was “Where the Hood At?” but it came on Cradle 2 The Grave and with a retirement announcement. So the next time the majority heard about him was an arrest: He’d impersonated a federal agent trying to steal a car at JFK airport, while in possession of crack-cocaine, other drugs and weapons, while he was with a female associate and her 12-year-old daughter. To recap, this was someone who at the time of arrest had gone platinum more than ten times over.

In 2015, DMX is mostly thought of as an elder statesmen to struggle rappers, and, unfortunately, an addict. It’s Dark And Hell Is Hot is remembered for its Tarantino body count, the “Anthem,” and for making me believe that Hell was a real place in New York controlled by Damien. There’s no denying his run that closed out the millennium, or his unimpeachable title as the best woofer of all time. When I listen to his music now, I like to imagine him how I did back then: He’s never lost a game of chicken in his life, and right this second he’s sprinting toward me, you, all of us, trailed by a pack of man’s best friends, barking “D(!)M(!)X(!)” — Brad Beatson

(#3) M.O.P – Warriorz

Regardless of the outcome of this poll,

M.O.P’s Warriorz is the hardest rap album of all time.

Let us count the ways

By

Zilla Rocca

1. The second single, and biggest hit of M.O.P’s career, was “Ante Up,” a song celebrating the joys of kidnapping men who wear jewels. I’ve seen chicks go batshit in clubs in Philly for 15 years straight when “Ante Up” comes on, let alone the remix.

2. “I’ll have your ass layin up for months, on a beat machine with a shit bag and a I.V., TRY ME MOTHERFUCKER!” – Lil Fame, “Warriorz”

3. The acapella of “Ante Up” is so hard that chopped up pieces of it alone made numerous Madlib and J Dilla beats gully by osmosis.

4. “YOU FUCKIN WITH THE ORIGINAL BACKSTREET BOYS!” – Billy Danze, “Calm Down”

5. True story: Lil Fame was walking through Brownsville in the rain, and found a pile of records spilling on the street. Fame grabbed them and found the Foreigner record that became the sample for “Cold As Ice.” M.O.P’s third single off Warriorz was literally built from the gutter.

6. “Brooklyn ya heard? I yapped the gold cross off John Paul III” – Lil Fame on “Calm Down”

7. There are five beats produced by DJ Premier on this album. You know what other beats DJ Premier made in 2000? Freddie Foxx “RNS,” CNN “Invincible,” Common “The 6th Sense,” Screwball “FAYBAN,” The Lox “Recognize,” and Big L “Platinum Plus.”

8. “FIIIIIIYAH!”

9. Unlike Mobb Deep, steely eyed nihilists with razors in their blood, M.O.P screams on your ass like your dad. They are the closest approximation to Run-DMC: a loud mouthed duo with boundless energy beloved by hardcore rap fans and crazy white boys with guitars. They even shunned jewelry and dressed fresh off the block. They make gym music, stickup music, fight music, and music to do drive by’s inside of a tank (remember the “Handle Ur Bizness” video?).

10. “Keep a rugged dresscode, always in the stress mode (THAT SHIT’LL SEND YOU TO THE GRAVE), SO?” – Billy Danze, “Ante Up”

(#7) Capone-N-Noreaga – War Report

I have never:

-

Stolen an 8 ball leather off of someone’s back

-

Sold pieces of wax in tiny zip lock bags to crack heads

-

Punched a cop in the face and ran because I was about to get caught violating my parole

-

Given a dude a buck fifty for snitching with a razor blade I keep in my cheek

-

Bribed an employee at The Athlete’s Foot a thousand dollars for a pair of Jordans three days before they come out

-

Kept a stolen gun with bodies on it and the grip wrapped with electrical tape in the glove box of my 92 Honda Accord

-

Bet huge sums of money on a pickup basketball game

-

Traded heroin for a blowjob

-

Smoked a blunt on the N train in the middle of the day

or snatched your chain off your neck in The Tunnel in front of your girl, because fuck it,, I’m hatin, but The War Report is the hardest album of all time because it makes me want to. — Abe Beame

(#2) Wu-Tang – 36 Chambers

Its Wu-Tang… this is pretty much a foregone conclusion. Even if you’ve never heard a single song from this album and I showed you the videos from it on mute, afterward you’d probably just hand me your wallet, watch and shoes on general principal. Now turn on the sound and cower before this assembly of personages dipped head to toe in Timbs, camo and leather, scowling to reveal gold teeth, brandishing guns and machetes. They tread upon the post-apocalyptic landscape of post-crack New York, which they call home. On this poisonous yet very fertile soil, they build their world out of scattered pieces of harsh ghetto reality, violent martial fantasy and drug-induced hallucination. Their mastermind and leader is a gangster nerd on angel dust–can you even fathom what kind of hurt a creative imagination on dust can conjure?

His right hand man is a ninja scientist. That one guy wear the mask is not in character, he literally can’t show his face in public because of outstanding warrants. Several of them have fangs. They play chess with human pieces and sharp objects. They joke about sewing your asshole closed for fun, and you wonder if that might be for the best because if you ran into them in a dark alley you would probably shit yourself. And you shouldn’t feel bad about that, because compared to Wu-Tang in 1993 we’re all a bunch of wet kittens. — Alex Piyevsky

(Play-in Game) Kool G & DJ Polo’s – Live and Let Die

At face value, Kool G Rap’s 1992 album, Live and Let Die, is the hardest in his entire discography, literally—its cover art depicts upward of a dozen felonies, including kidnapping, conspiracy, murder and even what appears to be animal cruelty. Its a grim, cinematic listen that plays out like an anthology of crime fiction—a much harder, less accessible take on The Great Adventures of Slick Rick. And what it lacks in mass appeal it more than makes up for in novelty.

Sir Jinx, best known for his production on Ice Cube’s early solo work, provides a largely dark, clamoring backdrop, over which G Rap marries the hardboiled quality of the title track from his previous album, Wanted Dead or Alive, with a thoroughly disturbing thirst for blood and debauchery. Outside of its lead single, “Ill Street Blues,”Live and Let Die is rarely canonized, but its influence casts a long shadow over both the horrorcore and mafioso subgenres, the latter being a conduit for several of the greatest rap albums of all time. —Harold Stallworth

(Play-In Game) GZA – Liquid Swords

I couldn’t stop staring at the artwork for Liquid Swords. Antic, slapstick violence is common in children’s cartooning, but the semi-realistic decapitations on the album’s cover touched one of my adolescent, humanist nerves. In the foreground, a combatant in GZA-logo’d hoodie is swinging a sword at the neck of his opponent, the blade on the verge of striking. The implied result is obvious. Still, there’s an unreleased tension. You never see the severed tendons or gushing gore of the soon-to-be beheaded, just the inevitability. This is what Liquid Swords is about: immovable, permanent tension.

The hook on “Cold World” serves as thesis for Liquid Swords:

Babies crying, brothers dying and brothers getting knocked

Shit is deep on the block

And you got me locked down in this cold, cold world

The universe of Liquid Swords isn’t just cold, it’s caked in black ice, gritty and reeking of dried blood’s iron-y aroma. This is brick through a window rap–the material trappings of late-period gangster rap are noticeably absent, substituted for holding cells, Carhartt jackets, and white knuckle pain.

Liquid Swords was stewarded by RZA (before he made a soul-stealing deal with Adrian Younge/Yakub), who produced the entirety of the album and recorded GZA’s vocals in his Staten Island basement. Liquid Swords landed squarely in the midst of RZA’s unimpeachable mid-90’s reign; the humble setting, GZA’s master penmanship, and RZA’s sample twisting atmospherics birthed an album dirt-caked and grimy. The Shogun Assassin sample that opens Liquid Swords makes it clear that violence is imminent–the sword’s been swung, the blade has momentum, and all that’s left to come is head-loosening impact. —Torii MacAdams

MIDWILD REGION

(#1) Freddie Gibbs – Midwestgangstaboxframecadillacmuzik

You’ve probably never been to Gary because no one ever goes to Gary. Gary brings to mind Treach describing East Orange: If you’ve never been to the ghetto, stay the fuck out of the ghetto, because you’ll never understand the ghetto. It’s the desiccated abandoned industrial city that can only emerge in the shadow of a larger metropolis that siphons all the glamour and money: Flint, Baton Rouge, East St. Louis, Newark, or the Long Beach and Oakland of the 90s.

“Chiraq” might be the poster child for American decay and municipal civil war, but Gary will never get that kind of attention. By virtue of that negative publicity, there is a perverse hope. Gary can’t even count on that. It’s been left for dead for too long. So was Freddie Gibbs, whose first post-Interscope project wielded the spurned maniacal retaliation you only see after you’ve been buried alive but somehow escaped.

It’s the sort of record many of us never thought we’d see again: A gangsta rap record built from the classical models, complete with dazzling cadences, hydraulic melodies, and lyrics that suggested that Gibbs laced his Backwoods with Makaveli’s ashes. (No Outlawz.) The first time I met him he waxed eloquently about the right and wrong way to rob a train.

Midwestgangstaboxframecadillacmuzik announced the birth of a Terminator assembled from the shrapnel of past greats: Pimp C, N.W.A., Bone Thugs, 2Pac, and The Dayton Family. But it never felt studied or stolen. Instead, it felt like he’d exhumed dead spirits and imbibed distilled ones to create the latest model of pure mayhem.

It’s been a long six years since it dropped. In that time, the genre has been partially resurrected through TDE, Vince Staples, Boosie’s return, Flocka, and the million off-base N.W.A. comparisons once ascribed to Odd Future. But Gibbs’ unofficial debut remains the most anti-social and unyielding of them all: Rap as battering ram and blunt trauma. Gary’s arsenal unleashed. — Jeff Weiss

(#8) Lil Durk – I’m Still a Hitta

Drill was a moment, but also a deluge: The scene produced waves of mumbly garbage rapping over cheap trap retrofits. Rising above the din was Durk’s I’m Still a Hitta, a collection of 14 songs, with, hooks and verses and stuff. Bad rappers use autotune as a crutch, but Durk has one of the stronger melodic senses in rap, so the effect for him is complementary, not corrective. “Rite Here” and “Jack Boy” are melodic gems of the highest order. “I Get Paid” turns what should be the stupidest hook in the world—“money/money/money/money/I get paid”—into a frenetic earworm.

I’m Still a Hitta’s cover is a pile of coke and a nine, and “L’s Anthem” is an aural nightmare in the best way, but to be perfectly honest, I’m Still a Hitta’s excellence doesn’t lie in its hardness. It lies in its sense of fun. No wonder Durk came out on top. — Jordan Pedersen

(#4) Bone Thugs N Harmony – E. 1999 Eternal

Before Young Thug, the rappers that nobody knew what the hell they were rapping about were Cleveland’s own Bone Thugs-N-Harmony. The group’s often impenetrable, signature flow might have been deeply melodic and fun to imitate but you would have to Babel fish to decipher what the hell they were saying.

A lack of a translator does not stop BTNH’s classic E. 1999 Eternal from being one of the hardest rap albums to ever grace a record store shelf. Bone Thugs were one part Eazy E and one part gangster Boyz II Men, E. 1999 simultaneously explored themes of violent gang life, the occult, an appreciation for bud and a deeper spirituality that pondered the heavens above.

Classics tracks like “1st Of Tha Month,” “Budsmoker’s Only” and Eazy E tribute “Tha Crossroads” made Bone Thug’s an unlikely crossover sensation in the summer of 1995 when the album dropped, selling a staggering five million copies nationwide and earning two Grammy nominations. More than critical acclaim and records sold though, E. 1999 Eternal is known for that innovative sound that could not only rule the charts but seem unflinchingly gangster in execution. After all, Cleveland is the city. — Doc Zeus

(#5) Dayton Family – F.B.I.

F.B.I. usually stands for “Federal Bureau of Investigation,” unless you’re in Venice Beach, buying a kitschy t-shirt. Then it stands for “Female Breast Inspector,” a recession-proof job if there ever was one. Of course, if you’re Flint, Michigan’s Dayton Family, it stands for “Fuck Being Indicted.”

Flint is widely known as a rusting, industry-less, largely abandoned shit hole—Dayton Family, named for a particularly crime-ridden street in the city, never tried to disabuse listeners of that notion. The group, comprised of members Bootleg, Shoestring, and Backstabba, debuted in 1995 with the hard-as-nails What’s On My Mind? A spot on an early No Limit compilation followed shortly thereafter, but Backstabba was imprisoned for 11 years, which member Bootleg claims was partially a result of him rapping about his misdeeds. He was replaced by Ghetto E for their second album, 1996’s F.B.I.

F.B.I. is much in the vein of the Southern gangster rap sound of the era: mostly sample-free, relentlessly pounding, and endearingly tinny. The mid-90’s is the sweet spot of hardness and occasional self- and sociopolitical reflection; alongside cocaine, this is what the Dayton Family traffics in. On “Posse Is Dayton Ave.,” Bootleg raps:

“In institutions, drug abusin since my younger days / Motherfuck a 9 to 5 my gangstas told me crime pays / I was 17 back in them days, I couldn’t spell diploma / But I could tell you bout good weed and crack cocaine aroma / Niggas my age not gettin paid, I thought that was dumb as fuck / Why y’all in school, I’m stealin bags of shit off Pepsi trucks.”

Shortly after the release of F.B.I. a perhaps overly poetic bit of irony struck—Bootleg himself was imprisoned for three years, further derailing the group’s momentum. The group reformed after his release, but F.B.I. remains the group’s pinnacle. If only he hadn’t been fuckin’ indicted. — Torii MacAdams

(#6) Twista – Adrenaline Rush

Twista’s 1997 album, Adrenaline Rush, is precisely that. It’s the terrifying whoosh you hear just before being sucked down the gravitational well of a black hole. Entirely produced by The Legendary Traxstar, the album bears his slow, booming signature sound. The production slinks with the grace of a jungle cat, and Twista, true to his moniker, barrels through each track at a Tasmanian pace.

What results is arguably the wordiest album to ever be tailored for subwoofers rather than earbuds. To be sure, there’s a few less-than-menacing tracks, like “Feels So Good” and “Get It Wet,” which, on a scale from Lil Zane to Lil Fame, register somewhere between Lil Twist and a post-Love and Hip Hop Lil Scrappy. But these jarring spikes in moistness are anomalies, easily offset by the album’s opening skit, wherein Twista exacts revenge on a man whom he believes to have murdered his cousin in cold blood. — Harold Stallworth

(#3) Eminem – The Marshall Mathers LP

“I make fight music for high school kids.” — Eminem

There’s a clear-eyed assessment from the blue-eyed rapper of what he did so well on The Marshall Mathers LP. An unmuzzled pit bull whose ability to rhyme made his juvenilia seem like Oscar Wilde (“Slimanus? Damn right, Slimanus”), whose schizophrenic posturing made him the avatar of all your twisted adolescent anger. That was Eminem, words like a dagger with a jagged edge, and enough skill at rhyming to distract you from the fact that he was mostly just picking on women and gay people. (Each of the lines I’ve quoted in this paragraph ends with a slur.) Em couldn’t play tough and be taken seriously, so he played crazy and it worked.

On the previous album, Slim Shady was everything. The alter ego bore a startling resemblance to the caged Ids of Middle American teenagers, but he was pure fantasy, dancing frantically out on the edge of the knife. Revealing that Slim Shady existed inside of Marshall Mathers was a dangerous thing for Eminem to do. Suddenly, the space between shooting paintballs at Insane Clown Posse’s truck and robbing a bank shrunk to the size of a pin. Was he a vandal, a criminal, or a psychopath? Or was he somewhere in between?

No matter where you came down, Eminem was untouchable — he was still sharp enough (and still cared enough) to tie his critics down with their own hypocrisy. Eminem was never even close to being the most dangerous person in hip hop. But for a couple of years he was the most dangerous rapper, vicious and unpredictable in equal measure and insecure enough to slash at anyone he saw standing in his way. — Jonah Bromwich

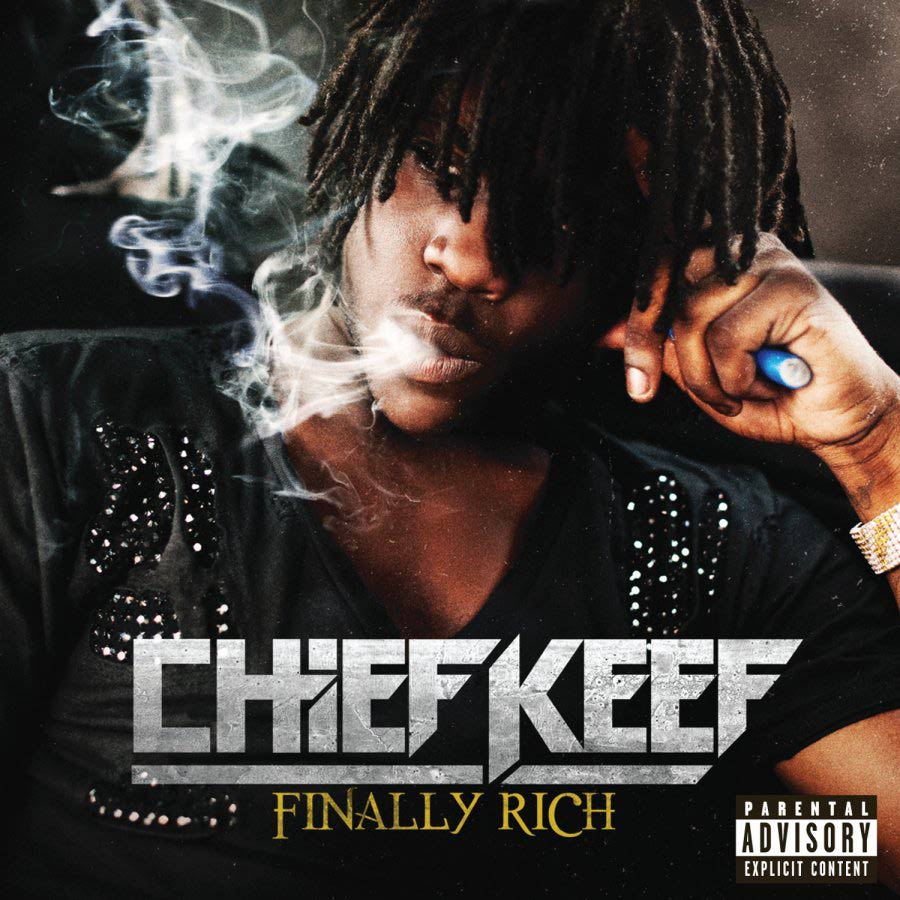

(#7) Chief Keef – Finally Rich

Chief Keef and Young Chop won with brute force. Clipped brass shrapnel, serrated strings, Satanist church bells stuttering like gavels, onomatopoeic growls, mangled throaty autotune like coughed-up arsenic—Atlanta trap as imagined by a cyborg blues singer’s drugged out rapper cousin on payday. That the punchlines and boasts came so concise, so bare, upset those with more rappity expectations for the midwestern streets that birthed the choppers, but ugly minimalism was always the point. “Broke niggas make me vomit,” Cozart said, on the song named after his child. It’s an apt artistic manifesto for an artist less interested in lyrical nuance than the tragic, jagged sounds of his own laughter and guns.

The details never mattered anyway. Chief Keef walked in the mall and simply bought all the stores because greed is an instinct, a survival tactic, not a shopping list. When cash is this fleeting, quantity over quality. “Everything designer, but it’s mismatch,” was an assault on jiggy dudes with time to plan out their outfits. Raris and Rovers, convertibles and Lambos, but really any foreign car will do. Keef only gets specific to talk about targets, Aiki, JoJo, all who threaten O Block. Guns clap, paper gets taller, for his mother LoLo, his daughter KayKay. The paranoid hedonism of a family man. Never has dad rap been so dangerous. —Tosten Burks

(#2) Dizzee Rascal – Boy In Da Corner

Dizzee Rascal comes from the ends not the hood. He was a stabbed not shot. He yelped out bars a decade before Danny Brown and Young Thug and provided the blueprint for the former. Forget that his U.S. audience was mostly composed of anglophile Urb readers, all that matters is that he was east London’s first urban star, a problem for Anthony Blair and a country that likes to sell itself as the home of Harry Potter and James instead of rampant alcoholism and low upward mobility.

E3 fucked with him, even if the album’s entire mission statement was that Dizzee desperately wanted to leave E3. Boy in Da Corner, once you parse the accents and slang, is the classic rise-to-the-top, by-any-means story, same as 50 or Biggie but untouched by crossover conceits or edge-blunting soul samples. Instead, the emotion comes from Dizzee’s tortured yelp while the mechanical sounds of cheap computer software whirr away in the background.

And whirr they do: the beats are dark, ugly, druggy monsters that are inspiring producers a decade down the line. Merging UKGarage to Three 6 Mafia’s sludgy southern hip-hop, Dizzee was doing monstrous basslines and unwieldly tempos back when most music critics were stuck lamenting boom bap. It even won a Mercury Prize, practically strong-arming tasteful critics into rewarding something that didn’t sound like a Blur clone. Now that’s gangster. —Son Raw

SOUTH REGION

(#1) Scarface – The Diary

“Off brand niggas can suck a dick, cuz they can’t fade me.”

In 1994, no one could fade Scarface, be they on- or off-brand. The Diary is the apex of Scarface’s hardcore continuum, the culmination of a hell raising half-decade which began with Scarface joining the renamed Geto Boys (no “h”) in 1989. The Geto Boys immediately drew the ire of Tipper Gore, Bob Dole, and their pearl clutching cronies at the PMRC with the group’s debut Grip It! On That Other Level. That said, it’s not hard to shock a woman who’d likely deny having ever farted and a man whose waxen personality complimented his oily skin. Their follow-up, We Can’t Be Stopped, featured Geto Boys member Bushwick Bill on a hospital gurney, his eye destroyed from a failed suicide attempt. The same year, Scarface’s Mr. Scarface Is Back debuted. Its cover: a shotgun-heavy Mexican Standoff.

The Diary was released in a year laden with great rap albums, and it’s to the album’s credit that it wasn’t critically overlooked. Scarface dialed back a tiny bit of the wanton violence, and further emphasized a mix of social awareness, street reportage, and B-movie gore. “Hand of the Dead Body,” featuring Ice Cube, a chorus from Devin the Dude, and production work from Mike Dean, directly addressed gangsta rap’s perception by the mainstream media.

“David Duke’s got a shotgun / So why you get upset cause I got one / A tisket a tasket / A nigga got his ass kicked / Shot in the face by a cop, close casket / An open and shut situation / Cop gets got, they wanna blame it on my occupation.”

The equally classic “No Tears” is outwardly violent, the type of song to court censorship, but its hardness is derived from its verisimilitude. The chorus-less song opens with Scarface leaving a funeral, removed enough from the occasion that the tears have dried. Like the cycle of black-on-black murders particularly prevalent in the early 1990’s, the song ends with Scarface vowing “You can cry but you’ll still die/There’ll be no tears in the end.” Scarface has nothing to offer but something approaching the truth–if you can’t take it, you’re probably Tipper Gore. — Torii MacAdams

(#8) Young Jeezy – Thug Motivation 101

Gangster rappers used to show you their neighborhoods, extol their hood credentials, and weave crime dramas. Young Jeezy largely didn’t do any of those things and it made him hard as fuck.

Thug Motivation 101 represented the new order in post-50 Cent gangster rap, or as it came to be known, trap rap. Jeezy is the trap. You know because he says it. You know his punchlines are funny because he adlibs laughter. Any salient details are incidental. Liberal arts students hated it (until they found out they could compare Jeezy to Upton Sinclair), but apparently the dope boys went crazy.

TM101, known otherwise as the Principia Trapmatica, appeals to Freddie Gibbs, ScHoolboy Q, and the kids in the Good Kid, M.A.A.D City skits, because Jeezy shovels brag raps that double as drug dealer axioms.

Take any line on the album and it’s an ice cold Instagram caption in 2015: “You better call your crew, you gon’ need help. / Whole car strapped, and I ain’t talking seat belts.” Then Jeezy leans into a mean adlib.

Every idea on the album is expressed in the title. It’s aspirational, but not in a Bad Boy, Roc-A-Fella, or MMG way. TM101 is distilled street shit, purified of narrative and character and Jeezy is a paragon of hardness. Also, Snowman is a pretty fucking hard nickname once you get over how dumb it sounds. — Evan Nabavian

(#4) Geto Boys – We Can’t Be Stopped

The Geto Boys didn’t bring horror to Houston. It was already there, waiting for them. Backed by sample-heavy boom-bap, Scarface penned more incisive and deranged rhymes in his early twenties than most do in their entire careers. High school probably would’ve hindered him and he knew it. Bushwick Bill and Willie D proved equally crazed counterparts. The former is the closest rap will ever get to Chuckie, possessed and pint-sized. The latter was as articulate as he was aggressive. Together, they rendered the horrors they knew intimately with visceral and penetrating detail. They pushed flour and pressed enemies whenever and wherever. They also took their animus to the soapbox, raging against Bush and the Persian-Gulf War.

“Mind Playing Tricks On Me” cemented their place in the rap canon. In five minutes you get a Rorschach in landscape. Paranoia, love, hatred, regret, fear and everywhere they bleed into one another. The group’s seminal single on what is arguably their best album, the song illustrates why the Geto Boys were great, why they were hard. All of the nut hanging and homicides only begat more nightmares—they weren’t scared of being afraid. — Max Bell

(#5) 8Ball & MJG – Comin’ Out Hard

Somehow, a Google image search for Comin’ Out Hard doesn’t yield anything remotely pornographic. Instead, you’ll find rows of JPGs featuring two men from Orange Mound, Memphis driving a drop-top through Houston. They are 8Ball & MJG. They had women tonguing their genitals while they gripped Tec-9s. They make everything on YouPorn look soft.

The Memphian duo featured the Houston skyline on the cover of their 1993 album in part because they were on Tony Draper’s Suave House and in part because they recorded it in Houston. Still, Comin’ Out Hard embodies the then crime-ridden city of Orange Mound. It is the sound of men raised on Stax trying to make stacks by any means necessary. You hear it in the soul samples; you feel the anguished delivery, the kind of pain only bred in the darkest nights on the Bayou. The definition of “hard” is amorphous, but the binding ethos is creep or get creeped on. The degree of hardness matters more than any concrete definition. Pimping, robbing, or riding on your enemies is hard. Quitting your job at McDonald’s to serve customers from the corner is harder. It pays more, but the price is higher.

Comin’ Out Hard isn’t the highest grossing 8Ball & MJG record. It’s not the most critically acclaimed, and it’s arguably inferior to their next two efforts. But it was first. It was for Memphis. — Max Bell

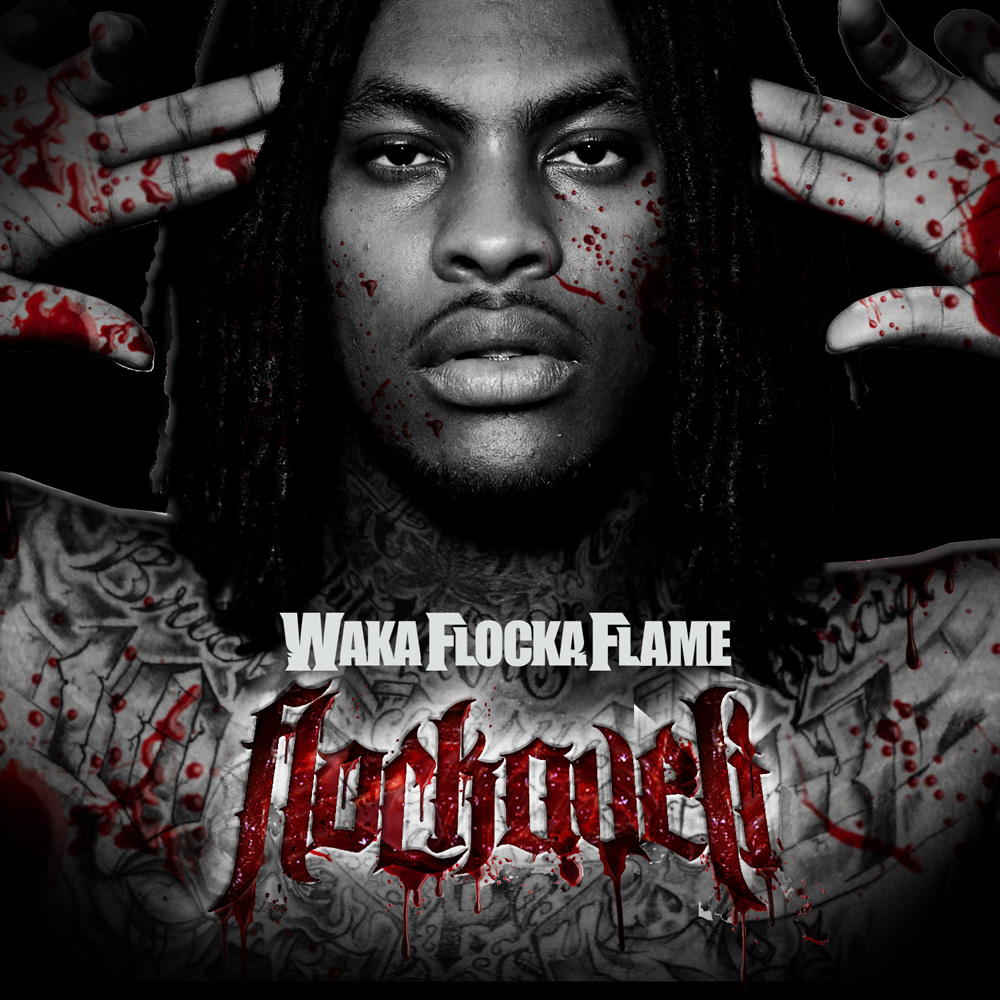

(#6) Waka Flocka Flame – Flockaveli

Waka Flocka’s Flockaveli is to hip-hop what Cro-Mags’ Age of Quarrel is to punk: the most uncompromising, aggressive, loud, and flat-out physical record of its era, taking whatever puny bullshit that had come before it and clobbering it with its auditory Hulk Hands. Sure, there had been aggressive Southern scream-rappers before Flocka burst unexpectedly into rap like a tentacle in a hentai porn, but none had been so dedicated to uncompromising, blunt-force-trauma aggression as the scion of the untouchable Mizay Management Empire.

The most remarkable thing about Flockaveli isn’t just producer Lex Luger’s Great Wall of Sound or how “No Hands” inadvertently resuscitated Wale’s career, it’s how beloved the record was for its time. Flocka and Lex Luger cowtied mainstream hip-hop and completely changed its sound, leaving behind a legion of imitators in their wake who couldn’t quite capture the mojo of the originals. Flocka flowed over Luger’s beats the same way an industrial mower flows over a field of steel beams, his threats, adlibs, and bizarre asides jumbling together to create a record harder than frozen carbonite. — Drew Millard

(#3) Three 6 Mafia – Mystic Stylez

Some things you can be sure of in life: Drano will clean a clogged sink. Chicken soup will cure the common cold. And Three 6 Mafia’s 1995 debut will turn any evening stroll into a journey through the catastrophic murk of your own urban nightmares.

In it the Mafia slices and dices through plenty of demonic slasher-flick imagery. But everything feels that much darker because it’s grounded in reality: Here’s DJ Paul talking about hitting the club and working MPCs in “Da Summer,” and then there’s Gangsta Boo promising total obliteration in “In Da Game” (side note: “I’m outie with your fucking soul” is really the best use of the word “outie”). And then there’s the eerie keyboard riffs and low-slung gutter beats, which have that classic dusty ’90s feel and through the cruddy lo-fi mix end up resembling shadowy movements in a ‘hood with no streetlights.

DJ Paul once assured readers of this site that he and his cohorts aren’t “devil worshippers or anything like that”; in fact, he and Lord Infamous had their musical start in the church playing gospel standards like “Amazing Grace.” But this Memphis posse sure started something with this album’s smoked out demon-dance ceremonies—it’s hard to imagine tracks like Tyler, the Creator’s “Radicals” happening without it. —Peter Holslin

(#7) Boosie & Webbie – Ghetto Stories

Let’s be clear: there is actually nothing harder than finger fucking with your diamonds on. It’s the hardest substance coupled with the most obscene and painful sexual torture that the Marquis De Sade never invented. Somehow, Boosie, Webbie and Pimp C make it seem like immensely pleasurable hedonism. Then they’ll take pictures of it and send them to their homies locked up in Angola. Hardness and generosity are not mutually exclusive.

Let’s be even more clear: Ghetto Stories is on this bracket as a stand-in for every Baton Rouge album that probably could’ve dominated the entire Southern regional. New Orleans had No Limit and Cash Money. BR had the Concentration Camp. Do we really need to play this game? When C-Loc went to jail, like every single great Baton Rouge rapper has at some point (save for maybe Max Minelli), Boosie got scooped up by Trill and paired with Webbie, a teenaged gunman so savage that Boosie’s mom was praying for Webbie because “he wild with that chrome.”

Ghetto Stories was the 2003 debut. It’s hard in the terrifying craziness that can only come from teenagers without a conscience. N.W.A. were nihilists for capitalism’s sake. Boosie and Webbie were nihilists because they never knew anything else. Boosie is probably the hardest rapper to emerge since 2Pac died and if you don’t believe me, I have several notebooks from his murder trial to show you. But the truth is that you’re only as hard as the environment you’re raised in.

When I was in Baton Rouge, I took a trip on a Monday morning in May to see Garfield St (“G Street”), where Boosie was raised. Down by the levee, across the tracks. The street sign was flattened as though a hurricane had just hit. A portable basketball rim collapsed in the street. Most of the homes had boards on the windows. And a few teenagers pushed bikes across the street, absent from school even though it was in session, no fear in their eyes, no reason not to jack the next person who wandered past the tracks. It was the only time in my life I ever felt like I shouldn’t get out of the car in broad daylight. It reminded me of City of God. It reminded me of Ghetto Stories. —Jeff Weiss

(#2) UGK – Super Tight

“I’m from that Texas—I ain’t your blood and I ain’t your cuz.” Did you know where Port Arthur was? I didn’t. It’s about 90 miles due east of Houston, and it sounds like an awful place. Do you want to visit a city where Bun B picks your girl up ten minutes after you drop her at her front door? You think you should cross Pimp C? He was doing so bad, he had to sell his fucking Jag. (Rodney really fucked him up at first; at least he didn’t go home in no hearse.) The feds went there once, and even when Misters Freeman and Butler had to lay low, the Hall & Oates samples learned to scowl and the crack got stashed in big-ass coffee cans.

There are life lessons on Super Tight, and they fit in single text messages: It’s supposed to bubble; Tell Moody-Harris they’re gonna have to come and get him; Give me mine, give me mine. (Oh, Moody-Harris is the funeral home, the one at 5th and Dallas.) So what makes Super Tight so hard? Anyone can be from the hardest block in the most destitute city. But the then-young men of UGK come out shining, grinning behind wood grain while the world burns around them. Crooked cops lurk, jealous boyfriends blow up your pager, but you can’t sweat in the Mighty Ducks of Anaheim jersey. They came out in ’94. —Paul Thompson

WEST REGION

(#1) Ice Cube – Death Certificate

“Here’s what they think about you…” Ice Cube has been an avuncular movie star for so long that it’s no longer particularly salient to point out that he used to be the hardest. Cube’s acting career has been trading on the reputation he gained from being America’s most wanted rapper for so long that his rap career feels illusory—a different man might as well be wearing the skin of O’Shea Jackson.

Death Certificate is Ice Cube at his absolute hardest —an impressive feat in a catalog that contains three other classic albums. As a songwriter and rapper, Cube has never been more flammable with a track listing that looks like a bandolier of incendiary grenades strapped to the rapper’s chest..“Steady Mobbin,” “No Vaseline,” “The Wrong N***** To Fuck With” are amongst the many, many classic songs on the album.

Death Certificate is the type of dangerous, ice cold album that allows you to pimp Coors Light and kiddie movies two decades later without seeming corny. It’s the synthesizing foundation for Cube’s entire persona—the nostrils flaring, eyebrows curling radical that threatened to kill Uncle Sam, burn down the corner stores of disrespectful shop owners and dig your daughter’s nappy dugout. All while remaining unquestionably true to the damn game. — Doc Zeus

(#8) Above The Law – Livin’ Like Hustlers

Let’s be honest: NWA was a much better rap group than Above the Law. That doesn’t make them the hardest though. NWA was sold to white kids, which makes them safe by default. Meanwhile Above the Law had a guy called Cold 187um, which is a more substantially more threatening rap moniker than Ice Cube. You can’t argue with that logic. Above the Law didn’t need to shock anyone to sell records – they just had to drop stone cold G shit for the hood, and they did that without ever going on to star in family friendly comedies or sell headphones. I don’t even know what these guys are doing now but it’s gotta be either lamping around in mansions from rap earnings or sitting around in the hood waiting for a call from Dr Dre. Either way, that’s hard as fuck. — Son Raw

(#4) Eazy E – It’s On (Dr. Dre) 187 um Killa

Clocking in at just eight tracks and 37 minutes, Eazy E’s It’s On (Dr. Dre) 187um Killa was probably a rush release, but the reasons for its hastily put together existence are pretty clear: to be a full top-to-bottom character assassination of the Compton rapper’s one-time NWA accomplice, Dr Dre. Following the success of The Chronic and, especially, the “Fuck Wit Dre Day” video – which saw a character dubbed ‘Sleazy-E’ handed a contract from a shady label exec before ending up next to the Pasadena freeway with the sign ‘Will Rap for Food’ – this was Eazy returning serve, and he fires back with extra venom. The good doctor is mentioned on five of the tracks, most notably the vicious “Dre Day” rebuttal “Real Muthaphukkin G’s” where Eazy and his then-current crop of Ruthless signees lay waist to the ‘studio gangster’ and his entire Death Row organization.

As pointed out multiple times by E, a court ruling entitled him to a percentage of any new music Dre released over a six year period, meaning he was collecting cheques off even the dis tracks. What Eazy was less forthright about pointing out, though, was that It’s On (Dr. Dre) 187um Killa found him majorly biting at his nemesis’s sound. Still, G-Funk has rarely banged harder. From the booming drums and grief-stricken whistle of “It’s On” to the bugged-out weed anthem “Down 2 the Last Roach,” the record established Eazy as a nineties artist to be reckoned with. Tragically, it would be his last release, and west coast rap was left with a hole it would never fill. — Dean Van Nguyen

(#5) 2 Pac – Makaveli

Tupac Shakur made Me Against the World after the Quad Studios shootings; he made the Makaveli album after he died. It’s not just a posthumous record—listen to “Hail Mary” and tell me the vocal takes aren’t from beyond the grave. The 7 Day Theory was released some eight weeks after the world’s greatest rapper died in a Vegas hospital, yet on every track, there he is, defeated but defiant, bullet-riddled but bulletproof.

You think Prodigy slept easier knowing that “Bomb First” was made by a dead man? Jay was left to wander the halls at Marcy, tail tucked between his legs, Hawaiian shirt half-open. To paraphrase another revered rapper-slash-actor, 7 Day Theory isn’t just vitriol hurled at Pac’s enemies, but it’s that, too. “Toss It Up” could be a radio hit, until he’s taunting Puff and Teddy Riley and Dre (who’s “gay-ass Dre” at the end of the sentimental “To Live and Die in L.A.”).

Pac’s vocals on The 7 Day Theory play like a vicious, booming stream of consciousness, his beliefs, his point of view, even his threats coming into focus right in front of our eyes. “Look at me laugh at my competition flashing my jewelry/ You’d be staying silent if you niggas knew me.” The best 2Pac record is probably one of the ones with his given name on the cover, but Makaveli’s was the meanest, the most desperate, the one that couldn’t be killed. The hardest. Maybe ever. — Paul Thompson

(#6) Spice 1 – 187 He Wrote

The East Bay-bred son of a Black Panther bestowed himself with the name, Spice. It stood for “Sex, Pistols, Indo, Cash, and Entertainment.” Just the essential artillery. How hard was Spice 1? Hard enough to be Too Short’s most adamantine discovery. Hard enough to be one of the few with Kevlar street cred to clown 2Pac on the set of Gang Related when he was dressed up to play the role of a police officer?

If you look in the mirror and say Spice 1 three times, Robert L. Green appears and presses a pistol to your temple and a blunt to your lips. You better not cough. If other G-Funk albums remind you of parties and pimping, this only reminds you of riots, chalk outlines, and yellow tape. You need infusions of blood after one listening.

Dre needed to insert clips from an actual insurrection. Spice 1 merely needed to tell you about his visions of corpses and body bags, even flipping the occasional Jamaican patois just to bridge the gaps between Kingston killers and the dregs of Oakland. He kept breaking it down until we understood, but the cold-blooded ideas couldn’t be misinterpreted.

Just look at the names of these songs: “I’m the Fuckin’ Murder,” “Dumpin’ Em In Ditches,” “Gas Chamber,” “187 He Wrote,” “Don’t Ring the Alarm (The Heist),” “Clip & The Trigga,” “Smoke Em Like a Blunt,” “380 On That Ass,” “Mo Mail,” “Runnin’ Out Da Crackhouse,” “Trigga Gots No Heart,” “Trigga Happy,” “RIP,” and “All He Wrote.”

There is not a single ray of light on this album. The number of bodies per second qualifies for serial killer status. They could’ve just played this for Robert Durst and he would’ve confessed years earlier. But this isn’t horror-core gimmickry. This is the East Bay gangsta, 22-years and already an OG. He not only knows where the bodies are buried, he pulled the trigger and disposed of the corpse. No fingerprints left behind.

What really separates the hard from the homicidal is a mission statement: one song to sum up the sociopath. 187 He Wrote has at least two. There’s “Running Out the Crack House,” where Spice goes on a mission in search of the enemies who killed his friend. He gets caught and spits in the retinas of a crooked cop trying to steal his drug money. They sic a K-9 on him, take him downtown, and ask him to snitch. All the while, the crack rocks have been stashed in his mouth. He swept the 1993 Street Pulitzers.

Then there’s “Trigga Gots No Heart,” the hardest song from the hardest soundtrack from one of the hardest movies ever made (Menace II Society). Just watch the video and realize that O-Dawg was taking tips from Spice. Oh, and ‘Pac called 187 He Wrote the hardest album ever recorded. You calling him a liar? —Jeff Weiss

(#3) Dr. Dre – The Chronic

If you ask my mother what her favorite album of all time is (not rap album, mind you—album) she will tell you proudly that it is Dr. Dre’s The Chronic. As time slows while you begin to process this, gaze shifting from her shiny straightened hair to her blue eyes to her wide smile to her pink-painted fingernails and fuzzy socks, maybe you can understand why it’s so hard for me to call this album hard.

I was born in 1989 in Long Beach, California. I don’t remember a world before The Chronic—the swirling G-funk melodies on “Let Me Ride” and “Nuthin But A G Thang” are as much a part of my early memories as chocolate covered bananas and the streamers on the handlebars of my first beach cruiser. For my mom, Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, and Warren G were logical extensions of her music sensibility—Parliament/

And maybe that’s the hardest part of The Chronic, after all. An album that weaves together explicit stories of illegal gang activity with clips of the L.A. riots was able to shuffle into popular culture through the (laid-)back door. It became so inescapable that white America played it (at high volume, preferably in a residential area) at barbecues with its in-laws. Mom always held that my first words were “Love Momma,” but she’s a known liar and one warm night in Los Angeles while the two of us shared a clove cigarette and a glass of red wine she finally confessed that they were “Deeez Nuuuts.” — Haley Potiker

(#7) Ice T – OG

In their 2006 essay “The Making of an O.G.: Transcending Gang Mentality,” the Death Row inmates-turned-gang scholars Steve Champion and Anthony Ross argued that a true Original Gangster isn’t just any old gang member who claims seniority in a set, but a community role model who exhibits “commitment, struggle, intelligence, integrity, and wise counsel.” By that rubric, Ice-T definitely makes the grade and that’s clear enough on this 1991 opus.

In it, Ice shows off his street bona fides while at the same time delivering devastatingly precise sociopolitical analysis (“New Jack Hustler,” “Escape from the Killing Fields”) and linguistic provocation (“Bitches 2,” “Straight Up Nigga”). Though police brutality and institutionalized racism are his main targets, he also uses his clear, elegantly simple rhymes to attack the music industry, sending up the “sex sells” mantra in his “What About Sex?” skit with Evil E and dismissing rockist politics with the debut of his “black hardcore band” Body Count.

Production-wise the album has its dated moments—the gunshot samples in “Home of the Bodybag” sound more like somebody smacking a filing cabinet with a stick—but beats like the Black Sabbath-sampling “Midnight” draw out the tension. Coming out during a volatile period in American history, right after the Gulf War and the release of New Jack City and a year before the L.A. Riots, O.G. serves as a dose of brutal truth and a “Fuck you!” to a system in dire need of change. — Peter Holslin

(#2) N.W.A. – Straight Outta Compton

N.W.A. weren’t the first to commit street knowledge to wax. Instead, they were the first to prove that knowledge was more powerful and profitable than anyone (except Jerry Heller) could’ve imagined. For the latter reason, some argued that Straight Outta Compton was exploitative, that the narratives were carefully calculated shock fare. But they missed the point. Even though the album probably wasn’t unadulterated autobiography for Cube, Eazy, Dre, or Ren, the stories spoke for disenfranchised black men in marginalized cities across the country.

Compton became emblematic of every urban war zone, places where tanks demolished front doors, crack destroyed families, militant factions fought over state owned concrete, and police officers turned government sanctioned thugs and killers. Over Dre and Yella’s barrage of hard, funk-inflected beats, N.W.A. frightened white America into paying attention as much as they educated them, simultaneously inspiring future generations to do the same. When you’re double platinum with little radio play, when you’re banned from performing at concert venues, when the F.B.I. is on your dick, the past is irrelevant. —Max Bell