Paul Thompson got computers ‘puting.

Like the great prophets before him, Cam’ron foresaw his demise. Just check “Live My Life”, the ‘Pac-nodding, Daz-featuring fourth song on Come Home With Me. If you’re not listening closely—maybe you’re brushing your chinchilla, maybe you’re Harlem shaking near a hearse—it sounds like our favorite Diplomat raps “And I’m scary with the fifth, compare me to a .GIF”. The last word, of course, is supposed to be “gift”, but you’d be forgiven for the mistake.

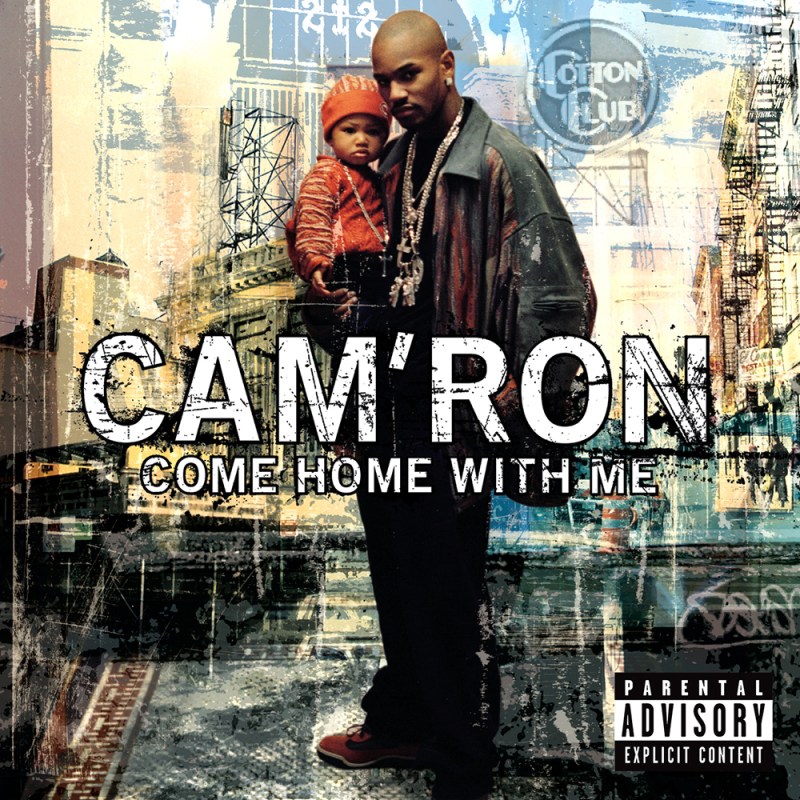

It’s not 2oo2 anymore. We’re now neck-deep in The Meme-ification of Cameron Giles, flush in imitators and novelty Ebola masks. Cam is a goofy weirdo, remade by the revisionists as a niche artist, a caricature, neutered. To quote the man himself: “Niggas tried to make Killa Cam all polite.” It can be easy to forget that at the turn of the century, Cam was unassailable, the ruthless killer who fell into an open vat of charisma as a child. Jay may have ruled the pop charts, but the streets (and the jewelers, and the fur dealers) were Cam’s. Fortunately, we have one last time capsule of Cam’ron the swaggering superstar: Come Home With Me, his Roc-A-Fella debut.

All the way back in 2001, when Jay was still dreaming up The Blueprint and wiping Un Rivera’s blood off his Pelle Pelles, Cam was plotting. The year prior, S.D.E. (Sports, Drugs & Entertainment) had hit #14 on Billboard and spawned a couple of minor hits. Unsatisfied, Killa demanded a release from Sony/Epic—allegedly by threatening to kill Tommy Mottola. He got it. Weary of the suits, Cam signed a management deal with Dame Dash, his childhood friend from Harlem. Naturally, this was parlayed into a deal with the Roc.

Come Home With Me occupies a couple of strange intersections. It has been documented ad nauseum how Blueprint introduced Just Blaze and Kanye West, revitalizing the soul sample template in the process. Both producers appear here, as they should—this is their natural habitat. Jay’s strength was always jumping on trends early, but the early-2000s Dipset heyday was built entirely by gun-toting chipmunks. You’ve probably heard the stories about “Oh Boy”: Jay had earmarked the beat for future use, until Cam and Juelz Santana jumped on it, took the rough cut across the street to Hot 97, and insisted they play it now. It probably cost the Harlemites, Just Blaze, and the label hundreds of thousands in royalties—the sample had yet to be cleared—but it was a metaphor for the Dipset modus operandi.

The second song on Come Home (and album proper) begins with a bizarre skit that doubles as the gulliest OnStar commercial ever recorded. “Losing Weight, Pt. 2” is another Just Blaze production, but it’s decidedly grimmer. “Eighteen months? Please, that ain’t ‘facing time’/I’m stressed anyway, need it for vacation time.” Before ceding the floor to his protégé, Cam runs the emotional gamut, from empathetic portraits (the girl who “felt life cheated her”), to smaller-than-life struggles of his own (“all them hot summers I was cooped up in the kitchen”1), all the way to kingpinhood. And he does it with color; are you afraid of Cam? No? What about his eight hundred invisible men? What about that girl from earlier, the one whose mother overdosed before she met Cam? Well, she’s killing rival dealers for him now. Welcome to the album.

The window dressing is decidedly of its period (the intro is “featuring Kay Slay”), but in most ways, Come Home With Me is inimitable. Structurally, sure, it’s a mess: Whimsical Aretha Franklin samples spin crack tales and break the word “Disney” into three syllables. Jokes about venereal diseases are blown up into six-minute sing-a-longs slash public service announcements. But on the micro level, Cam is at his tightest and most vicious. Peep how, on the title track, he distills a childhood’s worth of trauma into fifteen words: “I ain’t have no fresh clothes/or jewelry with the XO/My house had asbestos.”

We praise other rappers—up to and including the greats—for serving abandon or nuance, unfiltered celebration or unflinching naturalism. Cam blends those all together before breakfast. You probably remember “Hey Ma”, the Commodores-sampling single that hit #3 on radio. Cam’s verse is one of the densest, funniest, most brilliant turns to ever get played at weddings and bar mitzvahs. Framed as a conversation with his ex, Cam brags of being a “changed man” (“Look at the Range, ma’am!/I got a whole new game plan”). When she calls him on his bluff (“Looked and said, ‘That’s nothing but game, Cam’”), he gives up immediately, with the flossiest qualifier of all time: “She was right—she was up in the Range, man.” It’s funny, a little sad, arrogant, self-deprecating, and probably true, all inside four bars.

Other times, Cam injects the proceedings with a bit more menace. “Welcome To New York City” isn’t quite the Killa-Hov collaboration for the ages; we would never really get one. In what feels like his only misstep of the year, Just Blaze fashions the kind of faux rock-rap hybrid that no one really needed. On the first verse, Jay does the soulless social climber name-dropping thing (and who really cares that Michael Jordan was born in New York?). For whatever reason, though, Cam not only raps circles around his frenemy2 from Marcy, but rattles off one of the sharpest and most cold-blooded verses of his career. “You get jammed with them jammers, blammed with them blammers/Hot here—ask Mase, he ran to Atlanta.”

Speaking of his old Children of the Corn partner (and high school basketball teammate), Cam’s smirking face is carved next to Mase’s on Harlem’s Mount Rushmore. In fact, when it comes to rappers from Uptown, you could argue that only Killa himself bests Mr. Betha’s stylistic influence. Where the latter updated Kane’s internal rhymes and stuffed them in shiny suits, Cam stacked up syllables in an endless house of cards, reaching higher and impossibly higher. Then, somehow, at the end of the pattern, he would break form, but finish the rhyme with the most colorful phrase in the string. From “Boy, Boy”:

I’m a legend now, past the player

Pass the player, you got the rock? Pass that, player

I’m like Betty Crocker with cake—that’s in layers

Had city issues before, ask the mayor

He said “Cam’ron, please stop this crack behavior!”

He ain’t know, in ’96, I had a knack for gators

Anyone with a pen, dictionary, and a few minutes after Algebra can amass a list of rhyming words and phrases, and indulging that behavior can make for some truly insufferable music. What sets Cam’ron apart is that the rhymes feel secondary. Dizzying, sure, but each line is impactful in its own right. This is to say nothing of the tics for which Cam became famous: the inscrutable slang, the cartoon luxury, the onomatopoeia that’s more Joyce than Gucci Mane. “All my niggas got M-16s, kid/And all we do is watch MTV Cribs.”

Then there are the times Cam throws you headlong into his twisted imagination. “Stop Calling” is one long voicemail to the man he’s cuckolding, full of dead-eyed advice like “She’ll gas you up: ‘I love you, I swear to god we’ll go to counseling.’” (And how many songs open better than “Well, I’ma tell you straight up, homeboy, ‘cause it’s a cold world”?) Even “Oh Boy” is the product of a warped worldview; Cam and Juelz went on TRL with keys and hammers, they made you love them.

Come Home With Me is a twisted latticework of hollow points and tanning oil, still damp when you rip off the plastic. Even the deep cuts buried in the B-side are undeniable—the “Izzo” beat may have been snatched out from under him, but “Dead Or Alive” is pretty good as Kanye Consolation Prizes™ go. So it should seem misguided to end with the most tiresome rap trope, the tacit ode to fallen friends. But against all reason, “Tomorrow” is the perfect closer. Earnest and humble, Cam digs back. The first line is “I’ve been on both sides of burglaries”; he goes on to put himself in the shoes of his friends, his fiends, his female friends. It’s touching in a way you would never expect from Mr. “CEOs, all the frontin’ ain’t necessary/I fuck with secretaries”.

“Tomorrow” reminds you that outside the pink Range Rover is a cold world, homeboy. Come Home With Me launched Dipset as a veritable, if short-lived empire; two years later, Purple Haze would mark Cam’s creative peak. Since then, his name has been repurposed and trademarked, dragged through the digital mud, and, in the saddest cases, even forgotten. But just when you think he’s dead, when you’re tucked in bed in your Stephon Marbury pajamas, he’s cracking the door, waiting. “Hi, hater.”

1 “All them hot summers I was cooped up in the kitchen” was almost certainly the blueprint for Kanye’s “Lock yourself in a room, doing five beats a day for three summers.” Kanye, of course, is a certified Dipset superfan, whose only response to Cam and Jim Jones’ 2010 diss was to assert that the crew was “so necessary.” There is an alternate history where Kanye produces three J.R. Writer albums.

2 The Jay-Cam beef wouldn’t come to a public head until later in 2002, when Jay balked at Dame’s decision to name Cam VP of Roc-A-Fella, but the tension was palpable long before that. Is “Just Blaze, you owe me for this one” the most passive-aggressive ad-lib of all time? In Jay’s defense, he stepped up his game on that back-and-forth third verse; “Is this that thug from the Kit Kat Club?” And why, when you have two of the most gifted pop-rap writers in history on the same song, do you have Juelz Santana do the hook?